What is a measure in music? A measure in music refers to a single time unit with a certain number of beats at a certain speed of a specific tempo.

Measure

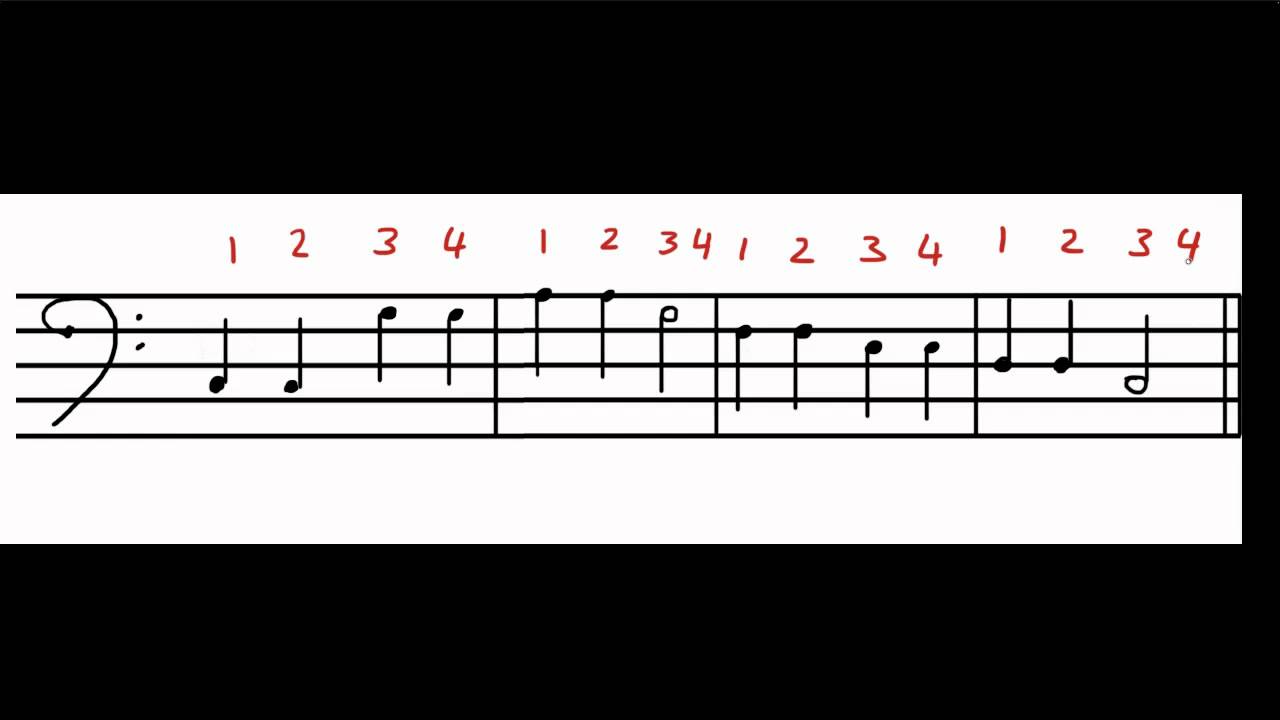

The measure is a time segment of a music piece determined by a certain number of beats. The bar separates each measurement. Beats are represented by a certain note value in each measure and vertical bar lines are the limits of the bar. Dividing music into bars regularly gives a reference point for locating a piece of music. It is also easier to follow written music because every bar of staff symbols can be played and read as a batch.

Barlines on the staff establish limits and structure and also might provide instructions for the musician. Two single bar lines, divided by two parts, or a bar line followed by a thicker bar line, which indicates the end of a piece or a movement, can consist of a double bar line.

A repeat indication looks like the finish of the song but has two points over one another that show that the previous piece of music needs to be replayed. An early repetition indicator can designate the beginning of the repetitive passage. If not, the repetition is assumed to be from the beginning of the piece or movement. This start-repeating sign does not work as a bar line, when it appears at the beginning of a staff, as no bar is before it; it just serves to signal the beginning of the passage to be repeated.

Measure in Music

A measure (or bar) in music theory refers to a single unit of time that has a certain number of beats at a given pace. Composers break their compositions into measures when they write music on a page—digestible chunks that assist music players to do the way they want. If a music composition is split into factions, the players only need to process a little music at a time, enabling them to focus on the greatest performance. Measures are specified perpendicular to the staff by vertical measurement lines or bar lines.

Long pieces of music can be organized into smaller sections. Professional musicians such as orchestra members and session players can read music in real-time and play a piece of music on their very first try. Composers split the music into smaller portions using bar lines that make visual reading simpler and perform better overall.

Reading of Measure in Music

A player reads music from left to right and plays the notes sequentially. You need to learn the fundamentals of tempo, meter, and note values for reading a measure of music. The information transmitted in writing depends on the following:

Time Signature

The number of beats per measure, and the duration of each beat, show the musical time signatures (the bottom number in the time signature). For example, 3/4 times show three beats each measure, and one-quarter note lasts for every beat. In western music, 4/4 or common time is the most prevalent time signature.

Tempo

The speed of a portion of the music relates to the speed. You can use beats per minute (BPM), or descriptive adjectives in metronome markings (traditionally Italian words describe tempo like adagio or andante).

Note Values

Individual notes for a certain part of the span of that measure last within one measure. For example, one-quarter of a 4/4 measure lasts, whereas one-eighth of the same 4/4 measure lasts. Eight notes last.

Bar Lines

Various sorts of bar lines signal diverse player behavior, from the repeat of a part to the entire music stop.

Time Signature

Time signatures are also referred to as meter signatures in written music. They assist us to determine which type of note is utilized to measure beats, and how many beats each measure is going to have. At the beginning of the piece, a time signature appears as a time symbol or stacked numbers in a musical score. Below are a few usual time signatures and how the staff is arranged.

The first instance is 4/4. In each measure, 4 beats are allowed and the quarter note symbolizes one beat. The number of beats at the top of the time signature says how many, while the number below indicates which note is one beat. A large C is sometimes 4/4 time, as it is also known as the common time.

The time-signature 2/2 denotes that the half note indicates one beat each measurement, and two beats per measurement are specified. The time signature 3/4 notifies a musician that a quarter note is a single beat (lower number), with three beats each step (the top number).

This page explains the fundamental principles of reading signatures and meters, shows how the different time signatures relate to one other and sound similar and different, and why composers can select time signatures over others.

Time Signature Sound

Music must be moved through time – it is not static, but it is essential for the music itself. So, across time, music is sound. This music through time arrangement is governed by time signatures in the western music system. Time signatures allow us to record our music so that we can play the music from scores, listen to its structures and speak to other musicians using similar terminology. As stated by the time signature, the organizing patterns of beats are the way we hear and/or feel the meter of the song.

When talking about music the terms “time signature” and “meter” are frequently used interchangeably, but time signing specifically refers to the number and types of notes in each music measure, whereas meter refers to how the notes are grouped into a repeated pattern in the music to produce a coherent sounding composition. Detailed strategies for categorizing the different time signatures into meters are explored later.

How to Read Time Signature

The time signature determines the number of notes allowed in each measure. As you have seen in the sample above of the time signature, each signature includes two numbers: one top and one bottom: 2/4, 3/4, 4/4, 3/8, 9/8, 4/2, and 3/1, and many others. The bottom of the time signature shows a certain note to count the beat, while the top note shows how many beats are in each measure. Seeing the American names from the above chart gives you a funny trick:

Take for instance the 2/4 time signature - you know that the 2 on top of the time signature is 2 beats for one measure, which leaves you with a fraction of 1/4 — the note long which you see in the time signature is a quarter note. You are therefore aware that in each measure there are two quarter-time notes:

- You know in 9/8 that 9 notes of 1/8 length are available in each measure.

- Each measure in 4/2 times has 4 1/2 notes, hence there are 4 1/2 notes.

- Thus we have three notes with a length of 1/1, so three full notes.

Common & Cut Time

The procedures above are how you find the most frequently signed notes and beats, but what about the letters? In truth, the two-letter signatures are shortenings and changes for the most frequent numerical time signatures, 4/4 and 2/2. The 4/4 time signature is so frequent that it has two names, the one being the 4/4 time signature, and the second the “common time” time. So when you observe music’s common time, you know that it’s 4/4 (which has as many notes as possible around how long).

The shorter common time is another prominent time signature. It looks very much like the signature “Common Time,” however it does not have a slash. Technically, these measures also have the so-called “Cut Time” in four-fourth notes, therefore the “C” will be slashed or “cut.” This modification in “Cut-Time” to “Common Time” means it’ll be twice as quick, thus the half note gets the beat instead of the quarter note! The cut time is as 2/2, written and utilized for quicker rates as 2/2.

Simple Time

Every meter whose fundamental note is divided into groups of two is a simple time. For example, Common Time, Cut Time, 4/4, 2/4, 2/2, 2/1, and more. These meters include: These meters are easy because the fourth note is equally divided into two eighth notes, the half note is divided into two quarters, or the whole note is divided into two and a half notes. If you refer to the preceding graph, you can observe these divides.

Compound Time

Compound time, which is a meter with a fundamental note division into groups of three, is rather more intricate. You instinctively realize that if there are eight as the lower number of your time signature, you are not in simple time. A simple 8-mark time would be useless as seen in the beat hierarchies and accents. So when you look at an 8 as the low number of your signature, you know you have to group your 8th notes into groups of three rather than two! In 6/8 there are three 8th note groups, but in 9/8 you have three eight notes, and in 12/8 there are four eighth notes. There are three eighth notes in three groups.

Technically, composers can employ a simple time signature to make a compound time sound and then mark every major beat phrase in three versions, which makes a duplicate division a threefold division, throughout work for the same effect. However, it would appear confused and confused to use triplets throughout a whole piece to obtain a compound time sound. While it is more frequent to see a simple signature for the music of the last 5 or 6 centuries in Western music with the two divisions, it was indeed a time that first developed and was noted! Since the notation of west music originated together with church music, many theories about music were theological. The most popular subdivision for meters was three in one in three compound or triple divisions, comparable to the Trinity of Christianity with the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit.

Irregular Time

The last option for beat division is to subdivide the beat irregularly or unequally. Although these meters are “irregular,” they do have patterns that the performer can recognize. Indeed, the most common irregular meters mix simple time and time in one measure together. Thus there are beats with three subdivisions and beats with two subdivisions in each measure. For example, the signatures as 5/8 and 7/8 are included. You cannot have equal groups of two or three eighth notes since there are 5 eighth notes per measure or 7 eighth notes per measure.

Therefore they are also beamed together in 5/8 and 7/8 to form an increased count analogous to 6/8, 9/8, and 12/8 in which the groupings of 8th notes are radiated to a bigger count. However, because the 8th mark is strange (and pre-eminent) in 5/8 and 7/8, the count lengths are unequal – or irregular in each measurement. The eighth note is normally identical, but as there are two counts and there are three eighth notes, they are irregular!

Types of Bar Lines

In sheet music there are different sorts of bar lines, each type denoting the beginning and finish of a measure and providing directions for the performer.

| Single Bar Line | A single vertical line that points to the end and the start of one measure. |

|---|---|

| Double Bar Line | Two vertical lines, side by side, indicate one portion end and another section starting. |

| End Bar Line | The second line is thicker than the first, with two vertical lines. This shows the end of a musical movement or a complete composition |

| Start Repeat | A pair of dots, resembling a column punctuation mark, follow double bar lines, the one thicker than the second. This shows the initial measurement of a section repeated. |

| End Repeat | A pair of dots that looks like a colon dot mark preceded by double bar lines, the second one being thicker than the first. This denotes a repeating section’s ultimate measurement. |

Classification of Meters

Each beat can be divided into two equal pieces in a single measurement. For instance, the quarter note is used for three beats per measurement in 3/4 times. Therefore, 3/4 is a basic meter and the quarter note can behalf in an eighth note.

Each beat can be split into thirds in a compound meter. For instance, the eighth note in 6/8 time signifies one beat and six beats per measurement.

Working of Musical Measure

One measure is the section between two rods of a musical staff. The time signature established by the staff is met by each measure. For instance, a song composed in 4/4 takes four quarter notes per measurement. Three-quarter beats in each measure will be per song in 3/4 time. A measure may also be called a bar; sometimes in common musical languages, written commands such as the Italian Misura, the French measures, or the German Takt.

In the music notation, there were no music bars and barlines always. In keyboard music in the 15th and 16th centuries, some of the early applications of barlines produce measurements. Even while barlines are currently creating measured measures, that was not the case. The barlines are sometimes used to split music portions for better readability. The methods began to evolve toward the end of the 16th century. Composers started to use barlines to design measures for ensemble music that would facilitate the ensemble playing together. When barlines were employed to make all measurements identical to the length of the mid-17th century, and time signatures were utilized to match bars.

Notation Rules

A measure will immediately cancel any adverse events, added to a note which isn’t included in the key signature of the composition, such as a sharp, flat or natural. One exception to this rule is that the accidental note is transferred with a tie to the next measure. The accident must only be stated on the first note, which alters the measurement, and each note continues to be altered throughout the measure without further notation.

For instance, you will have a sharp F-sharp in your key signature when you perform a piece of music in the G Major. Let us say that the composer wished to add a C-sharp to a four-point section. The initial measurement of the route could have three Cs. The composer simply had to sharply add to the very first C of the measure and the next two Cs will remain also sharp. But in this paragraph we had four measures, did we not? Now, the C-sharp is automatically canceled for the next step as soon as the bar line comes between the first and second measures, making the C a natural in the following measure.

This idea also applies to natural products written in one measure; notes to be naturalized in the subsequent measure are not naturalized until a fresh natural sign is again supplied. Again, the composer must utilize the example of a composition in the G Mayor to generate an E-natural, since the key signature naturally contains an F-sharp, in every measure of the work a natural sign must be utilized with an F.

Rhythm in Music

The placing of the sounds in time, in the music rhythm. Rhythm is an orderly alteration of contradictory parts in a more comprehensive meaning. The concept of rhythm takes place both in other arts and in nature.

There has been a great deal of discrepancy in attempting to define rhythm in music because rhythm has often been connected with one or more of its aspects, but not entirely independent, like accent, meter, and pace. Like with closely connected topics verse and meter, views on the nature and movement of rhythm range greatly, at least across poets and linguists. “Periodic” theories as to the sine qua non of rhythm are disputed by theories that even include non-recurrent movement patterns such as prose or plaintive.

Elements of Rhythm

In contrast to a painting or sculpture that is space-related compositions, a musical piece depends on time. In time, rhythm is the pattern of music. Whatever other components of music (e.g. pitch patterns or timbre) may have, rhythm is the one element that is fundamental to any music. Rhythm may exist without melody, as in the batteries of so-called primordial music, but without rhythm, it is impossible to have melody. The rhythmic framework cannot be isolated from them in music that has harmony and melody. The statement by Plato that rhythm is “an order of movement” is a practical starting point for analytics.

Beat

The musical time unit division is termed a beat. Just as one knows the constant pulse of the body or heartbeat, one also knows a periodic series of beats in producing, playing, or listening to music.

Tempo

Tempo is the rate of the fundamental beat. The slow tempo and rapid tempo expressions indicate the existence of a tempo not sluggish or fast but rather “moderate.” A moderate pace (76 to 80 pages per minute) or a heartbeat is supposed to be the normal speed (72 per minute). But a composer’s tempo of a piece of music is not absolute or final. The performance may differ in the size and reverberation of the hall, the size of the group and to a lesser extent, the sonority of the instruments according to the interpretive notions of the artist.

Rubato

The pace of work is never mathematically inflexible. The metronomic beat is impossible for any length of time to adhere melodically. A tempo tightening may be required in a loosely knit piece; a slackening may be necessary for a congested passage. Such tempo changes – i.e. “robbed time” – are part of the character of the music. Rubato requires the structure of an inflexible rhythm that he may leave and return to.

FAQs

1. What is the number of bars?

The staff is divided into bars (or “measured”), by vertical black bars called bar lines. The staff was divided into two factions. The stave was divided into two bars. Determine the number and type of notes contained in each measure.

2. What is the music of a measure?

One measure is a section between two bar lines on a musical staff. For instance, a song composed in 4/4 takes four quarter notes per measurement. Three-quarter beats in each measure will be per song in 3/4 time.

3. Is the same thing a measure and a bar?

While the words bar and measurement are sometimes interchangeable in American, the right use of the word bar only refers to the vertical line itself, whilst the word measurement refers to the beats between bars.

4. What are 4 actions?

Time signatures of 2, 3, or 4 beats per measure are the most prevalent. Those that have two beats are called double meters, those that measure three beats are known as triple meters, and those that measure four beats are known as quadruple meters.

5. What are 4 measurements of music?

The most frequent music meter is 4/4. The other name is so widespread and the two numerals are substituted by the letter C in the time signature. At 4/4, the numbers stacked say every measure comprises four beats every quarter.

6. How long does a measure of music take?

Look at this once again: This piece comprises three beats: 3 quarter or 6 eighth notes or any combination of three beats. Each measure can have three beats.

7. What is the timeline of music?

The time signature is a notational standard in Western music notes used to indicate how much of the beats (pulses) are included in every bar and what value of the note is to be shown on the beats. The signature is also known as the measurement signature or meter signature.

8. How can you read a music measure?

The highest number shows how many beats there are (think of the beat as the steady pulse of the music). The number below indicates which note receives a single beat. There will be 4/4 beats for each measure, or “common time,” and one-quarter beat.

9. What is called the space among bar lines?

A measure is called the space between 2 bar lines. Every song is separated into measurements.

10. What is known as a music bar?

A bar is a small part of music that contains a few beats. A bar (sometimes called a measurement). It can be considered a container. The timing of the song, usually 4/4, depends on the number of beats a bar holds.

Conclusion

So, you read time signatures like that! We have examined how they are different and similar, how they are employed, and how the music we hear can change. Many can sound and are interchangeable, although their origins or usage vary slightly. Meters are how composers organize and transmit music to the performers across time.

Related Articles

Yoga Music

Online Music Education degree

How Many keys on a piano